One of my favorite, enigmatic moments of early childhood comes in the form of question-asking. Usually appearing as a simple ‘why’ after an explanation, questions from young people signal both a wondering about the world and a sense of wonder that the everyday world can produce.

In his informative book, A More Beautiful Question, author Warren Berger illustrates the importance of questions for young people — especially people under age five. Writer Katrina Schwartz points to Berger celebrating the 40,000 questions children ask on average between the ages of three and five. Berger then shares the disappointing news that “right around age 5 or 6, questioning drops off a cliff.” While there are any number of reasons for questions becoming statements that are environmental and developmental, I want to use this brief post to celebrate those three years we all see overflowing with questions.

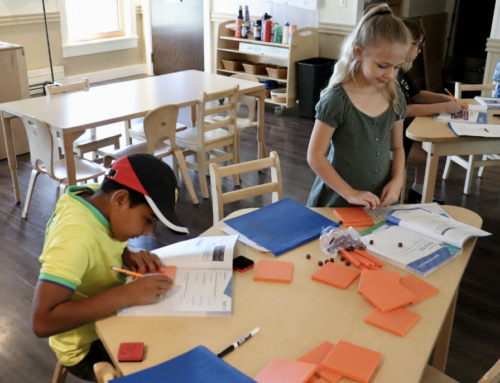

Many questions are seen as attempts at uncovering an answer — yet anyone who has had a conversation with a three-year-old knows that a single answer to a question is rare. Instead, a stream of whys threads together any number of responses that never seem to be quite satisfactory. Rather than looking at the realistic or frustrating elements of these conversations, what happens when we rotate our thinking into appreciating questions as an experience of wonder for children? What happens when we work from a place of not-knowing; relational curiosity? What happens when the world of a child is constantly expanded by possibilities found in conundrums and objects and relationships?

In a recent interview with Krista Tippett on the podcast ‘On Being’, cognitive scientist (and inspiration for another blog by our Head of School) Alison Gopnik puts our relationships with children into perspective: “. . . one of the things I say in one of my books is, if you want to get a little taste of sainthood, taking care of a 3-year-old is a pretty good way to do it. That’s sort of a joke, but not really, in the sense that that sense that you have of your attachment to children, that combination of ‘this particular being is the most valuable being on the entire planet, and I would do anything for this particular being.’”

When we as adults hold young people with such tenderness and value, we embody the sense of wonder and possibility that a vulnerable being can contain. What happens when we extend this type of tenderness to our understanding of a child’s world? Or even our own being in this big world? Everything around us can become lively and overstuffed with potentiality.

This exciting possibility reminded me of:

“There was a child went forth every day” from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass:

“There was a child went forth every day,

And the first object he look’d upon, that object he became,

And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part

of the day,

Or for many years or stretching cycles of years.”

Whitman’s words left me thinking about the role that space and objects play in supporting (or hindering) a child’s growth. They also helped me to pause and realize what an imprint the world around a child leaves on their internal being — maybe for a day or for years to come. I believe that when we push ourselves as adults to see the world around us with curiosity and care, with an openness to new understandings, we are beginning to recall the sense of wonder that held us rapt as young children.

Whitman weaves a number of ordinary experiences and things together to give the reader a sense of prosaic possibilities. He concludes by writing:

“These became part of that child who went forth every day, and who now goes and will always go forth every day,

And these become of him or her that peruses them now.”

The operative word, for me, is “peruses”. When children are given the time and space to peruse the world around them, they can grow into a sense of wonder that stands outside of time. They can grow into the moments and objects that they are surrounded by. They can model an appreciation for potentiality that is often lost on grown-ups. Let’s celebrate those moments and discover ways in which the tenderness we feel for children can be expanded into our relationships, our things, and the world around us. Let’s go forth in that way, every day.