Hello everyone!

“Take two letters away from this Beatles song to get the name of Paul McCartney’s 2002 Concert Tour and album of the same name.”

Do you know the answer to this question? Well, I didn’t, and it will always haunt me as the moment I saw my Jeopardy victory slipping away from me. Yes, that’s right, I was on Jeopardy – my 30 minutes of fame (quite literally). On a whim, I had signed up to attend an audition in Denver with a friend. And here I was on the Jeopardy set just a couple of months later.

I had done little to nothing to prepare myself once I got the call to be on the show. I had never really watched it regularly, and I was working full-time and had a six-month-old son, so studying was not a priority. I frankly figured I would have no shot at winning and so went with an attitude to just have fun.

And it was fun – I met a lot of people, learned a lot about how television production works, and got to meet Alex Trebek! But when it was time for my game, I was surprised to find that not only did I know some of the answers, I knew most of the answers. I was zipping through and soon found myself with over $10,000. I made a few mistakes along the way (most notably forgetting to say “What is..” when I provided my response – ugh!). But when we got to Final Jeopardy, I was in the lead.

My father (who had flown from Vermont to attend the taping) and I had talked incessantly over breakfast about betting strategies for Final Jeopardy, and I had had a plan for if I was in second place. But it hadn’t occurred to me that I might be the person in first place, and I had to think quickly.

And then the question came up, and I had no idea what the correct answer was. I took a wild guess and hoped for the best. When we shared our responses, I had a moment of excitement when my closest opponent revealed the wrong answer as well. But when he revealed that he had bet almost nothing, I knew I had lost. Since I had bet to cover if we both got the question right, I lost most of my money and therefore the game.

On the plane ride home and for days (maybe weeks?) afterwards, I couldn’t stop thinking about my loss and feeling a sense of deep disappointment. And I couldn’t figure out why it was bothering me so much, and that bothered me even more.

It turns out that what I was feeling is a common phenomenon called counterfactual thinking. We humans spend a lot of time imagining an alternative reality – what might have been. And what we imagine often depends on what alternative reality seems most likely. I just listened to a fascinating podcast called The Happiness Lab, which, as you’d imagine from the title, investigates research around human happiness. This particular episode focused on a study that found that Olympic silver medalists were, on average, less happy than the bronze medalists whom they had bested. Why would this be? It’s because of counterfactual thinking. The silver medalist is likely ruminating over how close she came to the gold – if it wasn’t for that one mistake, she would be standing at the top of the podium. On the other hand, the bronze medalist is two spots away from the gold and is much closer to fourth place, or no medal at all. She is thinking about what might have been in the other direction and is therefore incredibly happy to be where she is.

“Silver medalist McKayla Maroney making her now-infamous face at the 2012 Olympics.”

This isn’t surprising when you think about it – we spend our lives determining our happiness based on how we compare to others. Where do we rank in class? Are we driving a nicer car than our neighbor? Is our child walking before our friend’s child? But when we do this, we will inevitably wind up unhappy because there will always be someone doing better than us, and while we may occasionally “win” the comparison battle, we will always lose that war.

So what can we do to break out of this comparison habit? And how can we help our kids from falling into this trap? The good news is we have a lot more control over our happiness than we might realize. With some mindful awareness, we can shift how we view our achievements and our setbacks.

First, we can focus on the process, rather than the outcome. I’m sure you’ve heard the expression, “Life happens when you’re making plans.” When we worry too much about the ultimate goal, we don’t take the time to relish the smaller moments of victory on the journey. And when we pin all of our hopes on the product, anything less than achieving the exact goal feels like failure.

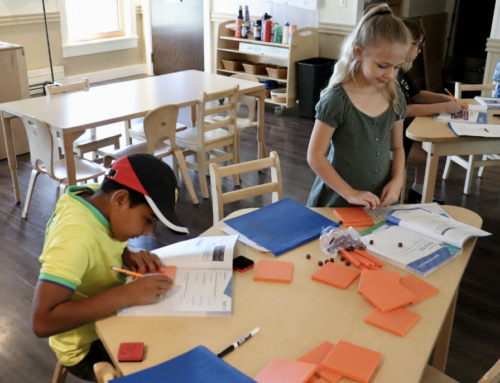

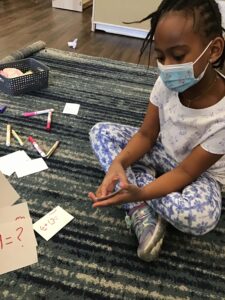

Second, we can remember (and help our kids remember) that losing is part of life and can be an experience for growth. At Compositive Primary, our teachers create several low-stakes situations where kids will try and fail multiple times. When kids understand that failure can be an opportunity, their perspective shifts and allows them to enjoy the process more deeply.

Finally, we can practice gratitude. Let’s go back to that bronze medalist – because she recognized how close she was to not winning a medal at all, she was grateful to be on the podium. Multiple studies show that when we take the time to be grateful, we are happier. This is a great practice to do with your family – every evening at dinner, have each member of your family share something they are grateful for. It may seem contrived at first since we don’t spend much time expressing gratitude, but like most things, with practice it becomes more natural and authentic.

So let’s go back to my Jeopardy experience. I began the day pleasantly surprised that I was even there, and so my expectations were low. But when I started winning and arrived at Final Jeopardy in first place, my perspective shifted. Now I could picture myself winning. And so when I saw that slip away, I couldn’t help but focus on what might have been and how close I had come. Ultimately, though, I was able to apply the tips from above, process my loss, and be grateful for the experience – my father had flown out to meet me, we had stayed with my best friend from high school, and I got to do something I love – answer trivia questions! When I reframed my situation, I was able to enjoy the memory for everything that it was and not just the outcome. And this has made me all the happier.

p.s. If you still want to know the correct response to the Final Jeopardy question, here it is: Back in the U.S. (or, more specifically, “What is Back in the U.S.?)

And if you’d like to listen to the podcast, click here.